Astros fans know better than to doubt Jose Altuve. The Houston legend has provided countless memories over his long career and will go down as one of the best Astros ever. While his 2022 postseason was underwhelming (a fact that did not deter Houston from getting its ring), his regular season was outstanding. In fact, by wRC+, it was Altuve’s best offensive season of his career. Better than his MVP season. While .300 felt like a given for younger Altuve, he hit exactly that mark for the first time since 2018. He did that while keeping his power up to par from the past couple full seasons. Is that production backed up by the underlying numbers?

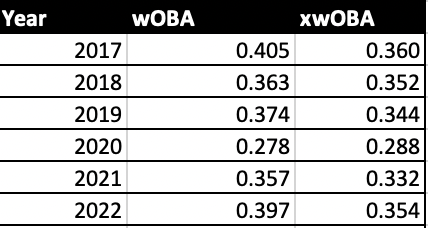

This is a question that doesn’t need to be asked about the Altuve’s of the world. He has proven himself more than enough for people to question if his success if “real.” Still, there was a cavernous 43 point gap in his wOBA (weighted on base average) and xwOBA (expected weighted on base average) in 2022. He got lucky?

Well, no one “lucks” their way into a 6.6 WAR season. However, the difference between his expected stats and his actual stats is not new. Aside from that shortened 2020 season, Altuve has consistently outperformed his expected numbers.

Since the start of 2017, Altuve has the 2nd largest gap in the MLB between actual and expected stats (minimum 1500 PAs). However, if it’s unwise to say Altuve built his 2022 season on luck, it’s even more ridiculous to suggest he’s built the entire latter half of his career on luck. He certainly isn’t just coincidentally beating his expected stats every year.

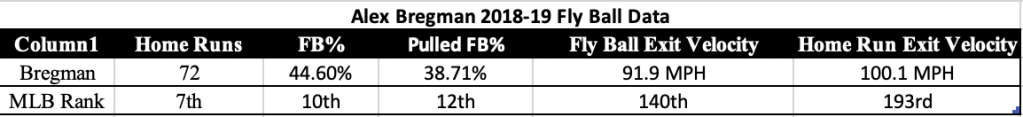

A few years ago, I marveled at Alex Bregman’s homerun totals. He hit 72 across 2018-19. While Altuve gets plenty more fanfare for power given his stature, Bregman is by no means an imposing slugger. Yet, he managed to rise towards the top of home run leaderboards. Bregman was ninth in total homeruns.

In August of last season, Eno Sarris of The Athletic reported that Bregman told him he’d hit 20 homers the rest of the season, or at least 20 doubles. The pulled fly balls would come back. The key! Back in his home run peak, Bregman actually led the league in pulled home runs in 2018-19. Like Altuve, Bregman produced massive wOBA-xwOBA splits in that span of time.

Of players who hit at least 25 home runs combined across 2018-19, Bregman ranked 195/198 in average exit velocity. Remarkable considering he ranked 7th in total home runs hit. During Bregman’s ascension, lifting balls to the pull side was the name of the game in baseball. Combine that with the juiced ball and many players with no expectation of big power began putting up big home run totals. Bregman was the king of that. Examine some of Bregman’s numbers below:

Bregman racked up homers in bunches, hitting a ton of fly balls and pulling a lot of them. On average, they didn’t leave the bat with much thump. That becomes more of a bonus than a requisite if you utilize park size. The fences are almost always at their closest down the foul poles. While no home runs are weakly hit, almost any professional baseball player can hit the ball say, 98-100MPH off the bat. Not everyone can consistently hit the ball 105+ MPH. If achieved at the right launch angles and direction, those 100MPH EV’s can often suffice just as well for power production.

That’s where the expected stats come into play. Statcast expected stats take the launch angle and exit velocity of a batted ball. Using prior batted balls similar to those values, they assign the expected wOBA from the probability the batted ball falls under each possible outcome. The odds that a batted ball is an out, a single, a double, etc. It does not consider directional or park factors. A fly ball down the left field line at Minute Maid is far more likely to leave the park than one towards dead center. Simply, a player can outperform their expected fly ball numbers if they can consistently pull the ball in the air.

Did Bregman just mostly take advantage of the Crawford Boxes? He actually hit 40 on the road, compared to his 32 at home. His strategy was successful everywhere. It isn’t just the short Minute Maid porch. I haven’t stopped marveling at Bregman’s power success since looking at his numbers during the 2019 season. That success is what led me here to Altuve.

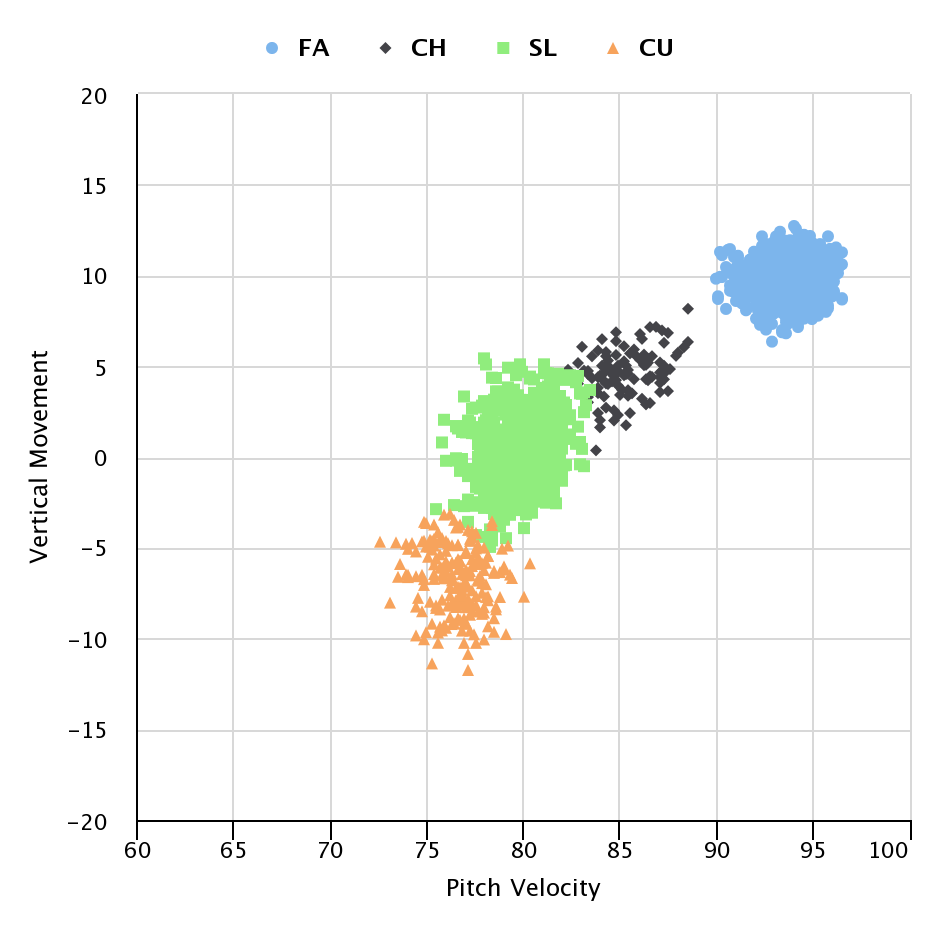

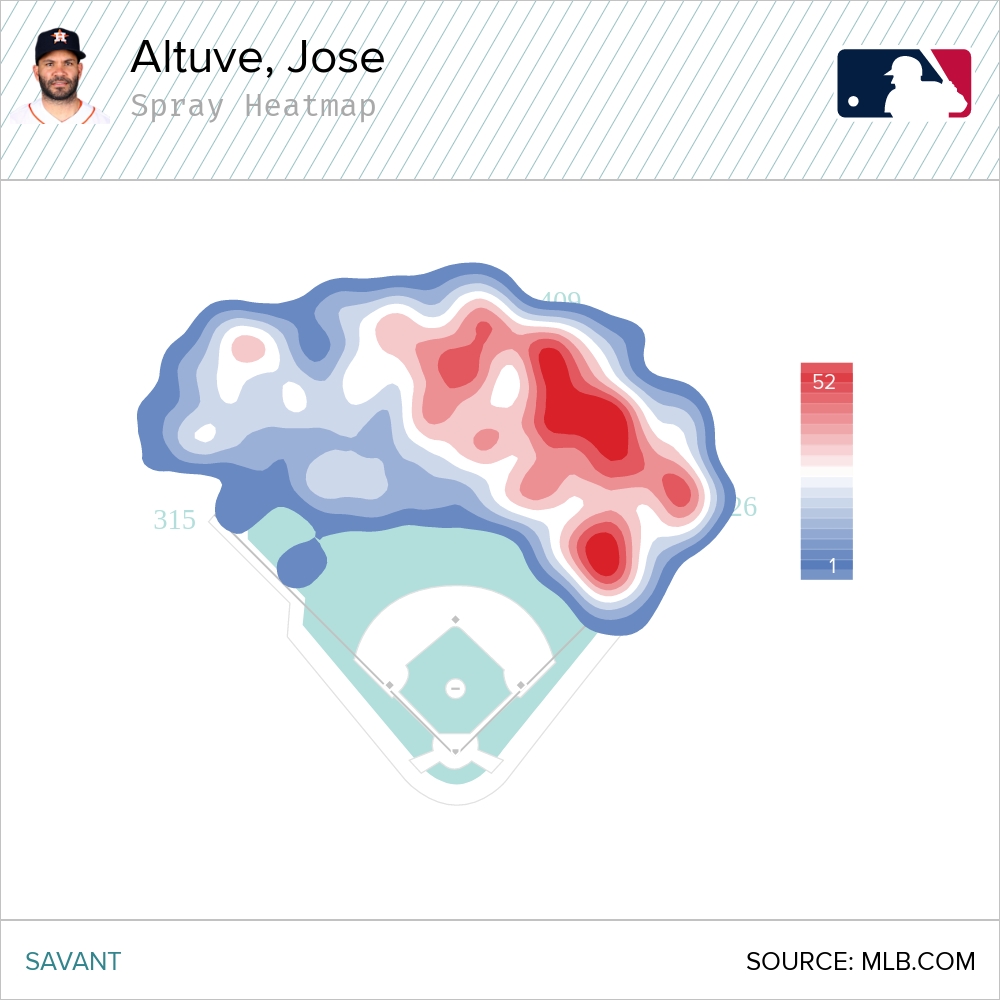

As he has aged, Altuve has consistently changed his game. The adaptability is an impressive trait, yet a necessary one to continue to have top-5 MVP seasons into your mid-thirties. While we may never see him hit .320+ again, he’s been quite successful in other factors the past couple seasons. A major part of this sustained success is a batted profile that looks quite different:

A lot of opposite field fly balls! That’s not uncommon, and it certainly didn’t prevent Altuve from succeeding in those years. Next, the same chart, but from the 2021-22 seasons:

The sample size is roughly half as large, so the data isn’t as tightly packed. Nonetheless, the shift from opposite field to pulled fly balls is striking. Altuve made a conscious effort to get around the ball in the air – a change from the younger version of himself.

There were hints of this in 2019, at least in the pull rate. Altuve – like the many in the league – ran a massive HR/FB with the juiced ball. The returns from that combo were 31 home runs. I tend to not put much weight into 2020 with the sample size.

2021 was a big step for the current Altuve. His fly ball rate spiked, and he ran a career high in pull rate. This returned another 31 homer season in a less advantageous offensive environment. However, his infield fly ball rate skyrocketed. He was the worst player in the league in that department, and his BABIP suffered as a result. In 2022, he remained on track with his pulled fly balls and limited the pop ups. Altuve combined that with a career low chase rate to ultimately put up arguably the best offensive season of his career.

Similar to Bregman, he hasn’t’t been successful by consistently crushing the ball. Since the start of 2021, Altuve ranks 20th in total home runs. He ranks 157th in home run exit velocity. His average exit velocity ranked among the likes of Miguel Rojas and Owen Miller in 2022. The overall batted ball numbers indicate a player with little to no pop. Yet, Altuve remains as productive as ever.

It’s quite an encouraging sign for a player about to enter his mid-thirties. He’s figured out how to marry pull power and patience. He still hardly strikes out. That’s a profile that could age quite well. Pulled fly balls have a very high correlation with success, and Altuve can fight other diminishing abilities by continuing to utilize it. Altuve and Bregman are both great examples of tapping into home run power while lacking the natural strength to consistently hit the ball hard. It’s a skill that will serve both of them well in the future if they are able to consistently harness it.