For Cristian Javier, it’s always been about the fastball. If anyone watched the Game 3 World Series broadcast, you probably caught on how to the constant discussion of his riding 4-seamer. The one dubbed the “Invisiball” for it’s unique deception.

If it’s always been about the fastball, it’s also always been about the strikes. Javier rode that fastball success to exceptional strikeout numbers in the minors, pushing him up the Astros minor league rankings as an unheralded international signing. He also walked more than 10% of batters faced at almost every level of the minor leagues. He was able to limit those walks in his first season in 2020, but his strikeouts dipped and he gave up far too many home runs. In 2021, Javier became the long relief ace. Still, he walked too many guys and gave up too many home runs. In 2022, he cut the walks down and slashed the home run rate. He improved all his numbers across the board, despite an increased workload. One stat in particular stood out to me.

As I mentioned above, Javier actually limited his walks in 2020, relative to his minor league numbers. But it certainly was not due to first-pitch strikes. Of every pitcher who threw at least 30 innings (half of what’s necessary to qualify), Javier was dead last in starting off an at-bat in his favor. The quality has remained:

In 2022, there was improvement! He threw more first-pitch strikes and cut his walk rate. Even still, he remained close to the bottom of the league in the former. How is Javier able to remain so successful while struggling to get ahead?

I will preface this analysis by noting that a first pitch strike is not a great barometer for overall success. It does have some general correlation with walks, but, depending on a pitcher’s approach and arsenal, it really could mean nothing. Patrick Corbin ranked third in first pitch strikes in 2022. I don’t think I need to lead you any further there. However, you generally are not finding the leagues aces at the bottom of this stat, and Javier has tended to operate at the extremes here in his career. So, let’s take a look how he has gotten here.

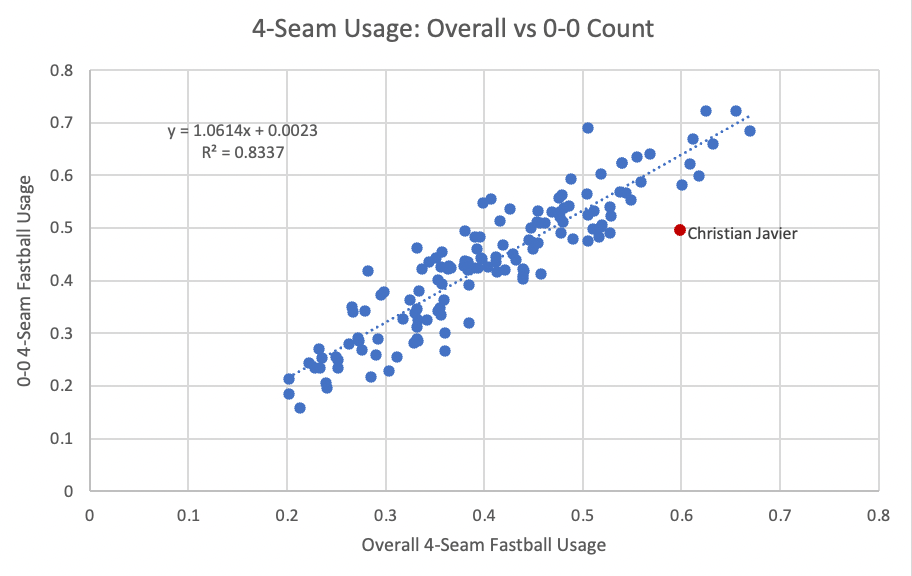

We’ve already alluded to Javier and his famous fastball. It’s a fantastic pitch. He throws it often – about 59% of the time. The connection there is simple. In a 0-0 count, a count that leans towards strike-throwing, one might expect Javier to focus on his great fastball. He doesn’t:

Javier’s fastball usage actually falls to about 50% on the first pitch. The above graph demonstrates how Javier separates himself from the group. Especially with guys who utilize their four-seamer more, it’s not often they change that tendency significantly in blank counts. Javier is different.

Besides being one of the best pitchers in baseball, Javier sets himself apart in another fashion. He’s one of few pitchers able to get by while relying almost entirely on two pitches. It’s generally accepted that a starter needs at least three reliable pitches to thrive – not the case for Javier.

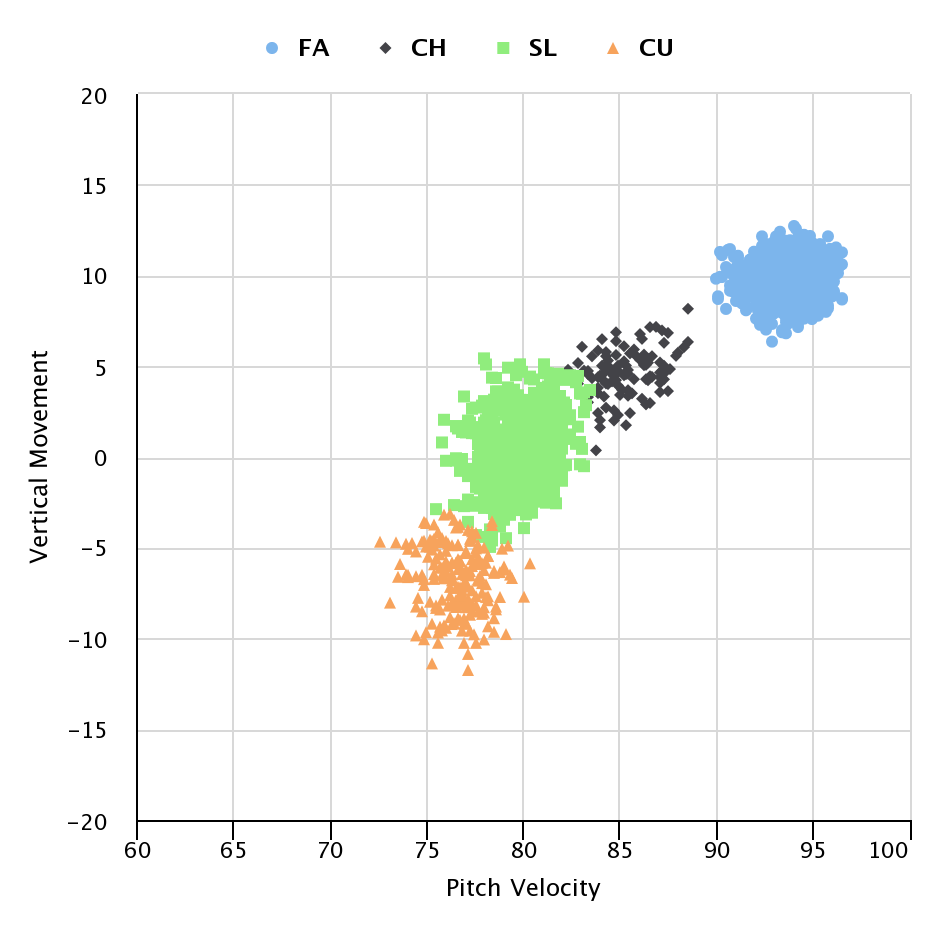

Javier has a curveball he throws around 8% of the time. It’s the third pitch in his arsenal, albeit not throw that often. If you take a closer look, not a lot sets the curveball apart from his slider:

The curveball is identical by its horizontal movement, but has extra bite compared to the slider. Javier takes off about three mph from the slider to the curve. It is a materially different pitch, but no one would fault you if you confused some of the breaking balls while watching a Javier start. The curveball did set itself a part in certain facets.

For one, over 90% of its usage was to lefties. That isn’t particularly strange. Plenty of pitchers have a pitch that they use almost exclusively to neutralize a platoon disadvantage. However, of all those curveballs to lefties, around 35% came in that 0-0 count. Javier threw about as many first-pitch curveballs as he threw in any two-strike count. While it was thrown sparingly overall, Javier had a clear purpose for his curveball. Balancing his arsenal to try and pick up strikes on lefties. Did it work? More on that later.

The curveball fits into a larger overall picture. A picture that indicates Javier likes to pitch a little backwards. It wasn’t just the curveball to lefties. He threw plenty of first-pitch sliders to lefties. Against righties, Javier favored the slider to the fastball. Javier’s breaking balls are meant to be the setup for the fastball, rather than vice-versa. With two-strikes, only Spencer Strider and Brandon Woodruff threw a higher percentage of fastballs. This isn’t an unheard of way of pitching, but it’s certainly unique.

Is Javier particularly adept at picking up strikes with his breaking balls? Well, as we discussed at the beginning of the article, it does not seem that way. Javier has been at the absolute bottom of the league at getting strikes on the first-pitch. I don’t think that matters to Javier. After this year, I don’t think it should matter to us either.

Consider Javier’s fastball. It neutralized hitters in many facets. Impressively, it was nearly untouchable inside the strike zone. Javier threw 832 fastballs in the strike zone this season, 18.5% of which generated a whiff. Only Eric Lauer surpassed that among starters. This begs the question – how significant is it for Javier to be ahead in the count early? Most pitchers want to avoid throwing a fastball in the strike zone while behind in the count. Hitters can sit on that. Javier doesn’t have to worry about this situation nearly as much as others. Even if they’re sitting on it, his fastball is still so difficult to hit. Missing with those early breaking balls just isn’t that much of a drag on overall performance for Javier.

Javier loves his fastball. The way he mixes it in with his other pitches is different. Against conventional pitching tendencies, Javier throws more breaking balls early and finishes batters off with his fastball. A lot of those breaking balls miss the strike zone. As a result, he may end up in more 1-0 counts than most pitchers. With the results he put on the table this year, he proved that doesn’t matter.